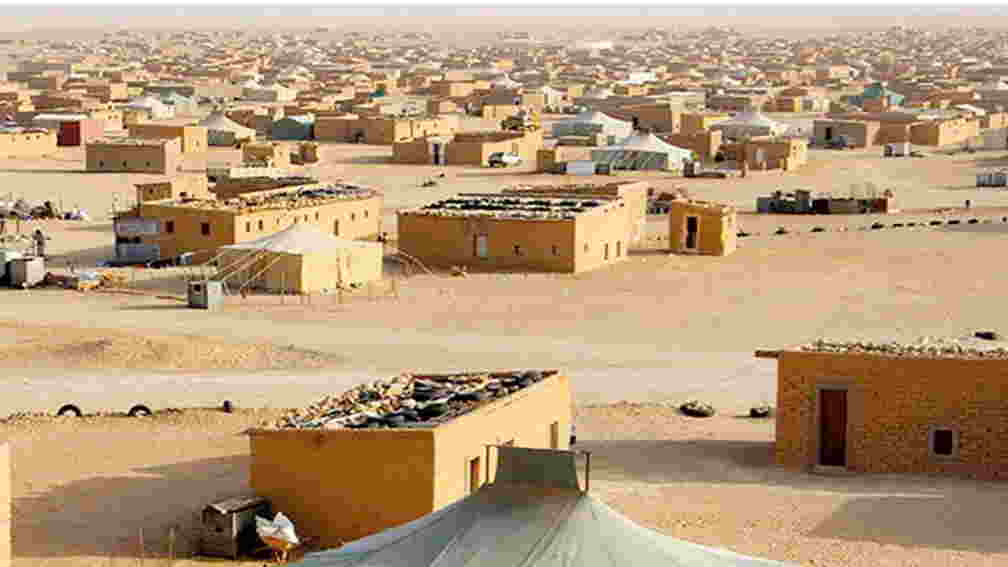

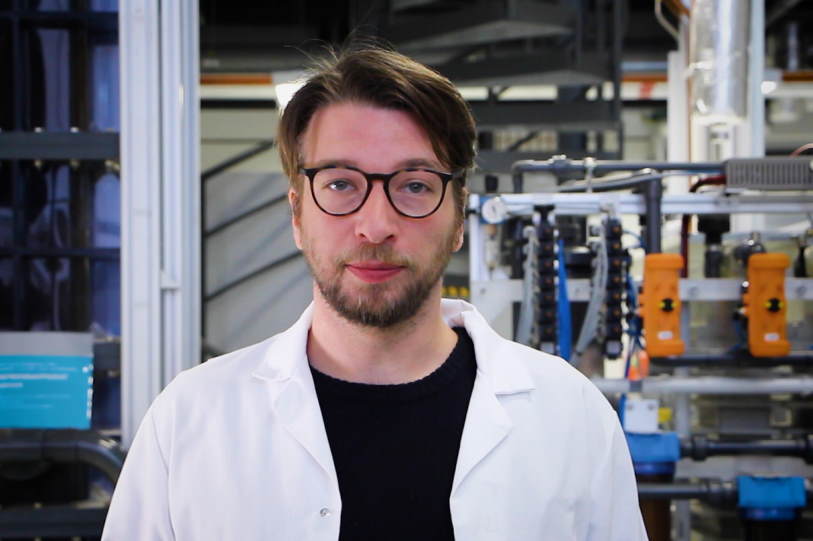

Since 1976, tens of thousands of Sahrawi have been living in refugee camps in the middle of the Sahara, near the city of Tindouf. These people are almost entirely dependent on aid. Based on a project by local agricultural engineer Taleb Brahim, who uses a hydroponic system to cultivate feed for livestock, the team at GreenUp Sahara now wants to further develop these systems to grow other plants, as this method of cultivation uses significantly less water than conventional crops. Despite stiff competition, the GreenUp Sahara project won the Fraunhofer Alumni Award by a wide margin, and received 10,000 euros in prize money. In this interview, Marc Beckett, water technologies and resource recovery expert at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB in Stuttgart, explains where the greatest challenges lie and which further steps are now being taken. He also describes the adverse living conditions faced by people in the camps.

Mr. Beckett, how does it feel to be the first Alumni Award winner?

I feel proud and quite excited! I was and am very impressed by the other projects that applied for the award. The weeks in the run-up to the vote were extremely exciting, and I never expected that GreenUp Sahara would win the prize. But what’s most important to us is that this will enable us to continue the project. We have had significant problems, particularly due to the effects of the coronavirus during this last year. Among other things, we could only communicate with Taleb, the scientist we work with on site, to a very limited degree. Eventually, we managed to get back in regular contact with him and the World Food Programme. The prize money gives us room to maneuver: Without the award, we probably wouldn’t have been able to continue the project.

The Fraunhofer alumni will be glad to hear that; not only did many of them vote for the GreenUp Sahara project, but they also co-financed the prize money with their membership fees.

What’s actually really exciting about this project is that this area still hasn’t been particularly well researched, scientifically. That’s why it’s also really worth our while to link up with other researchers. For example, we are in contact with the University of Liège and the University of Hohenheim, in order to make advances on both a scientific and a project level.

Urban farming, indoor farming, and hydroponics are in vogue, and lots of start-ups have been launched in this area in recent years. Big companies are jumping on the bandwagon as well. There’s a lot of research potential in areas like energy efficiency, automation, and specific plants.

What’s different about GreenUp Sahara?

At this point, I’d like to make it clear that we’re not developing a completely new concept here. Hydroponics is already widely used commercially in the Netherlands, for example. There’s a reason that little country is one of the largest agricultural exporters in the world. Hydroponic facilities, that is, facilities where plants have their roots directly in a nutrient solution, use mineral nutrient solutions that are produced industrially. However, those aren’t available for our use case in the Algerian desert. These solutions are a limiting factor when it comes to using hydroculture, not just in Algeria, but in other regions, too. We want to extract these nutrient solutions from raw materials that are available locally, using processes that will work even under the limitations of this desert settlement. And of course, we also want to avoid taking resources away from food production.

What are the biggest challenges here?

Our focus is on creating hydroponic nutrient solutions from waste material. The biggest issue is that depending on which plants are available, or which animals, or more specifically, what feed the animals are given, you’ll get completely different nutrient levels and so an incredibly high variability in the input materials. That means developing a recipe or formula for this solution is really complex. On top of that, there are hygienic factors. Meanwhile, the fact that we can only simulate real-life conditions to a limited extent in the labs is a challenge for us, as we’re subject to different requirements here from in the Sahara. So, we carry out our research in close collaboration with Taleb on location. It wouldn’t make sense to develop unrealistic processes that work in lab conditions, but can’t be implemented in the field. And of course, the pandemic and its travel restrictions are posing further challenges.

Have there been any developments yet?

We’re experimenting with blood meal, for example, and meat and bone meal, which we ferment using bacteria, but that produces a very strong smell. We’re carrying out these experiments at the institute, in rooms that are also used for other purposes and have certain standards that need to be met. Of course, the ideal would be if we could carry out these experiments on location.

How did you come across this project?

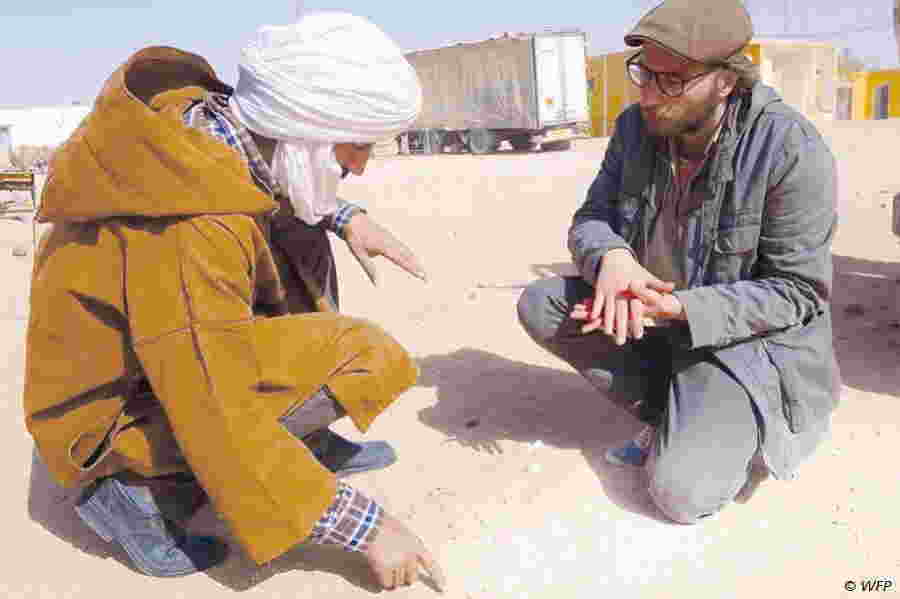

In 2017, I had just completed my master’s thesis at the IGB when I was asked to take part in Fraunhofer Venture’s FDays, the predecessor to the technology transfer program AHEAD. That led me to working on hydroponics with the World Food Programme, which is how I got to know Taleb Brahim. I started focusing more intensely on the topic and then, in December 2017, we finally spent a week on site.

Taleb had learned about the germination of barley grass from a video online and built a similar system with help from the WFP. Since then, more facilities of various sizes have been built under his supervision in Algeria and other African countries.

How important are these facilities?

These grass mats are used as feed for livestock, roots and all. The local people’s diet mainly consists of milk and meat. As refugees, the herders have to stay in one place and can’t move to different grazing grounds like they used to. Without that fodder, the animals have to eat waste, like cardboard.

The seeds are imported to the camp via food programs, like all the goods there, in fact. One possibility would be to produce these seeds on site, but then we come up against the issue of the nutrient solution again. Incidentally, experiments with different types of barley and wheat, and other varieties like alfalfa are underway.

In the next step, we want to advance the cultivation of vegetables and crops. Because until now, the diet in the camps has not been very varied, and that in turn causes health problems such as diabetes.

Do you expect to be able to transform these research results to other regions?

You probably can’t transfer the results on a one-to-one basis, because other locations have different resources and conditions, and therefore different nutrient levels. But our goal is to get a feel for which processes and which input materials work. I can’t promise a formula that can be used worldwide, but we want to get closer to principles that can be transferred. In the medium term, we can certainly contribute to creating formulas more quickly.

That’s why we’re also involved with the WFP’s H2Grow platform, where teams are working on similar problems and questions, such as which substrates or plants can be used, and of course there are experts who are applying these findings in practice on location. Incidentally, we shouldn’t forget that climate change and the already noticeable water shortages it’s causing in Germany are also helping topics like the circular economy gain new relevance in our own country. One of the projects Fraunhofer IGB is involved with is HypoWave, where we’re researching how urban waste water can be used for producing crops.

Could the local people use this to earn an independent income? Aquaponics is another interesting approach. In addition to ensuring food supplies, the “Ich liebe Fisch” (“I love fish”) project, which was another applicant for the Alumni Award, is about creating new sources of income for farmers in Malawi.

There are some exciting possibilities here. However, one question is how centralized our approach should be. Should each farmer have a hydroponics facility or would it make more sense to have cooperatives or small companies, considering the complexities involved? With hydroponics, of course, local start-ups might be able to produce these nutrient solutions and sell them to farmers. That would be an exciting approach to the situation in the Sahara. And that’s also one of the reasons we’re concentrating on looking for raw materials that are very cheap or can be acquired for free. Of course, processing, quality, consistency, quantity, stability, and the bacterial activity in these nutrient solutions are also important considerations. But I actually know of at least one example from another crisis region where a nutrient solution is being produced and sold locally.