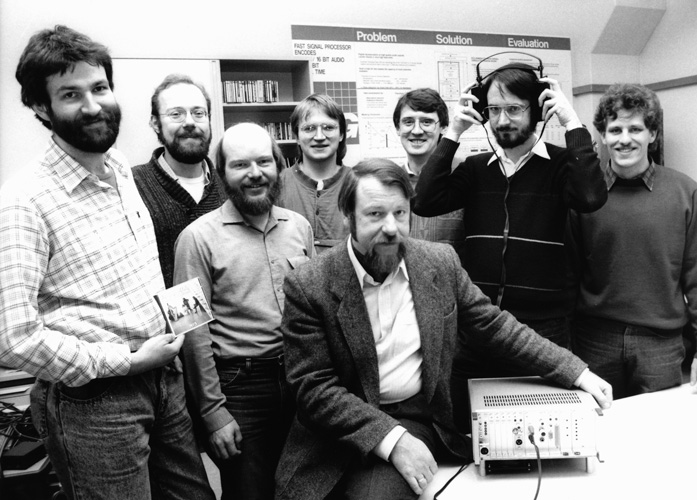

Finding an inductee into the “Internet Hall of Fame” among the ranks of Fraunhofer alumni is no surprise: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h.c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg is one of the inventors of the MP3 file format, probably the most important development for the music industry since the invention of vinyl records. Over a year ago, he resigned as director of Fraunhofer IDMT to enjoy a “not-so-retired” retirement, as he puts it himself. Not content with just being a senior professor at Ilmenau University of Technology, the founder and CEO of Brandenburg Labs has also been enthusiastically working on “the next big thing”: PARty, quasi the acoustic equivalent of virtual reality. In addition to creating a perfect auditory illusion for the listener, the device serves as an acoustic magnifying glass or filter — essentially, it will allow the user to block out or listen closely to specific sounds. The possible applications are plentiful, but the project is still a long way off from being market ready. While the researchers are facing many challenges, as an investor and researcher, Brandenburg has not been scared off. As with the development of the MP3, this new project is the work of a relatively small, tightly knit team.

You have made a major contribution to the digitization of music. However, in recent years, despite being pronounced dead multiple times, vinyl is thriving once again, contrary to all predictions. Mr. Brandenburg, when was the last time you listened to a record?

A vinyl record? It was definitely more than 25 years ago. We did too much research into this area at Fraunhofer IIS for me to give any credit to the supposed advantages. These are all psychological factors that have nothing to do with the sound quality. People can recognize records due to the background noises, and when combined with the haptics, optics, and other factors, this makes people feel good. People who like that prefer vinyl records, but not me.

But is it not true that psychological factors are very important when it comes to listening to music?

One thing we can say with certainty on this point is that what you hear is very much based on what you expect. We can’t get away from that. Our brain has a superb ability to match patterns. The ear is constantly making comparisons with things we have heard or experienced. However, other factors apart from memory also affect our perception, such as our current surroundings or our feelings. So, we evaluate variants based on personal taste.

Let’s stay on the topic of perception. You have probably listened to “Tom’s Diner” more than anyone else. Why was this song by Suzanne Vega such a major challenge in particular?

The MP3 format does not rely much on psychological processes. Instead, it uses our knowledge of how the ear works. On the format side, we draw on signal statistics for efficient coding. This is what we call masking and is more intense when music uses a wide range of frequencies or is very complex. However, this is not as strong with individual sounds. These effects cancel each other out to some extent. The brain analyzes what it hears particularly critically when it comes to speech. Speech consists of both the voice’s fundamental frequency and the harmonics, and the algorithm encodes these elements separately. Speech signals also have a very wide range or frequencies, or bandwidth. In the case of “Tom’s Diner,” the algorithm reported that it would need four times the available bit rate.

However, you and your team managed to solve even this problem in the end. But let’s take a look at the similarities between the business models for vinyl records and for MP3s. In both cases, the majority of sales was determined by the content and not by the technology. Is that not the classic marketing problem?

If you look at the role of the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft, then you have to explicitly refute that. Perhaps we didn't outstrip Dolby’s sales, but we did achieve significant revenue from patents. On that point, I would also like to quote an American CTO of a large technology group, and a friend of mine, who declared to me in early 2000: “You know Karlheinz, you Fraunhofer guys have been the only ones in this area who understood the business models of the Internet.” At first, I took it as flattery. But with hindsight, I believe that he was not entirely wrong. According to the rules of the market at that time, companies that invested 100 times as much in their marketing budget for comparable technologies should have been the ultimate winners.

Millions of people were using this format. Did providers have to follow suit?

This was a course that was set even before the MP3 was standardized. In the late 90s, some organizations were competing for this market. As I said, they had massive marketing budgets, but most importantly, their technologies were only a little behind the MP3. Believe me, we celebrated when the last of the major players, namely Microsoft and Sony, finally adopted the MP3. What did Fraunhofer do differently? We looked at areas of the market where precedents had already been set. When it came to transferring music files, RealNetworks, a Microsoft spin-off, had created a decoder and encoder that could be used to prepare content and make it freely available on the Internet. It sounded awful to begin with. However, it did allow people to listen to music on a computer, which was not very common at this time. We followed this example. We made the decoder, that is the media player, available for commercial use at a very cheap price on PCs (not media players like MP3 players or smart phones). Our plan was to launch the encoder on the market at a very high price. However, an Australian student stole the encoder library and put it online for free — “on the dark web” as it's called today. Eventually, we dropped our prices massively and entered into contracts with shareware providers. With Thomson, we had the right industry partner on our side. At that time, there was a manufacturer in Germany called ITT Intermetall that at one point had a global market share of over 95 percent with their MP3 decoder chips. As part of an industry project, we assisted the company and profited from the success of the MP3 player through licensing revenues.