Targeting the private sector

An example from Hong Kong shows just how perfectly fake worlds can work. An employee of an international corporate group there sat through a whole videoconference with multiple employees of his company – but it was all fake. His alleged colleagues prompted him to transfer almost 24 million euros to the people behind the scheme. They had evidently hacked into the company’s internal video records beforehand and used AI to generate voices to go with the videos. The target of the fraud did not notice that he was the only real person in the conference until afterward, when he talked to his real boss on the phone.

Scenarios like this one could become more commonplace in Germany in the future as well. The German Federal Criminal Police Office published a report on the national cybercrime situation in 2023 this past May. The report shows that the number of crimes committed from other countries against victims in Germany rose 28 percent from the previous year. The attacks caused 206 billion euros’ worth of damage.

Disinformation is the world’s biggest issue today

“The most significant challenge of our time is not climate change, the loss of biodiversity or pandemics. The biggest issue is our collective inability to distinguish between fact and fiction,” concludes the Club of Rome – the well-known organization that, over 50 years ago, denounced the environmental impact of economic growth. The consequences of digital manipulation are loss of trust and a polarized, uncertain society where people can no longer agree on fundamental facts. Where trust erodes, people tend to believe information that confirms their own viewpoints. And that further shrinks the factual basis available for democratic discourse. With all these factors in play, it is little wonder that 81 percent of people in Germany think disinformation is a danger to democracy and social cohesion, as this year’s study titled “Verunsicherte Öffentlichkeit” (Unsettled Public) from the Bertelsmann Stiftung shows.

Sixty-seven percent of respondents believe disinformation campaigns originate with groups of protesters and activists, while 60 percent blame bloggers and influencers and nearly half say foreign governments are at fault. The study also permits a comparison with the United States, where uncertainty about and perceptions of disinformation are even more pronounced than in Germany. While 39 percent of Americans surveyed worry about being deceived by disinformation themselves, so they are increasingly verifying content with a more critical eye, Germans firmly believe in their own judgment, with only 16 percent saying the risk that they might be influenced by disinformation themselves is high or very high and 78 percent saying it is low. This self-confidence could prove to be misplaced now, with the new possibilities created by AI.

Where AI can help to identify deepfakes

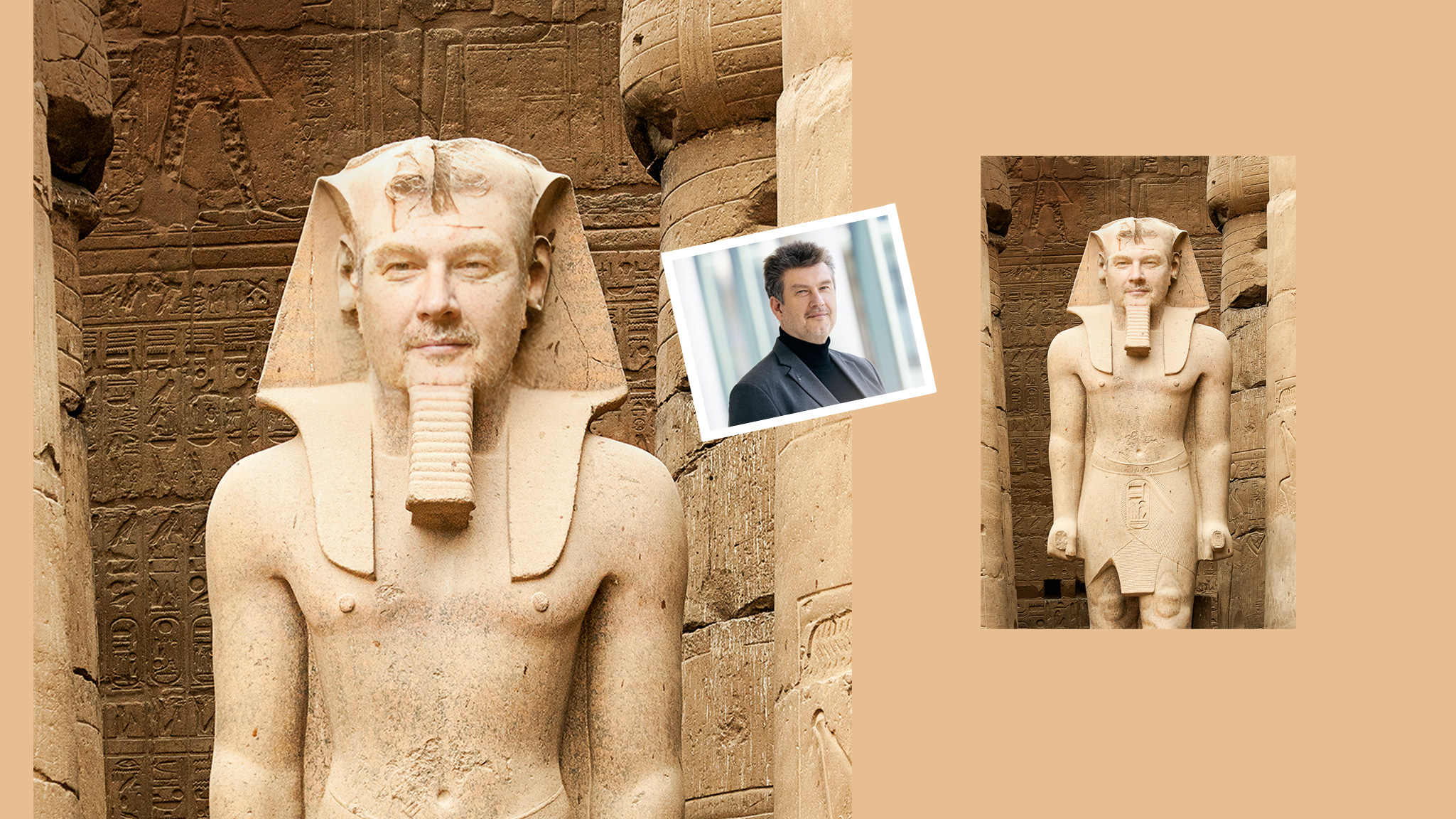

There are a wide range of methods used for manipulation. In face swapping, two faces from different photographs are simply swapped. In facial reenactment, a person records a fake text and remotely controls a target person in a real video with their movements and gestures – in real time. “What is new is the ability to use voice cloning and lip synchronization to create convincing videos of any kind of content,” says Steinebach, the forensics expert from Fraunhofer SIT. “Existing videos are simply given an AI-generated fake soundtrack, and the lip movements are synchronized to match.”

To recognize images or videos that have been manipulated in this way, Steinebach and his team rely on a combination of deep learning and traditional signal processing, which can help to identify the blurry or slightly washed-out structures in an image that are typical of deepfakes. “We measure the frequencies of certain sections of the image and compare them to other parts, such as the background. If there are any discrepancies, it could be a sign of a fake.” Since deepfakes only replace one area of a real video, that area also has different statistical properties, which can be identified using a more advanced pixel analysis. If only the soundtrack is changed, not the video itself, recordings that are already known are often easy to find using a reverse image search. One telltale sign is if the gestures are the same, but the movements of the lips differ.

Automatic detectors: caution warranted

There are already a number of AI-based detection tools on the market that promise simple, cheap technical solutions. But how realistic is this idea of reality at the push of a button? Steinebach warns against relying on online detectors in videoconferences or browsers. “The error rates are still too high for that, and it would cause more uncertainty than benefit if there were constant warnings.” Instead, he argues that these kinds of solutions should be used only in conjunction with the eyes of multiple trained experts. Forensic reports that incorporate additional factors, such as sources, falsification scenarios, plausibility checks, and potential circumvention strategies, offer significantly greater certainty. But owing to the cost, these kinds of analyses are typically commissioned only in areas that are especially critical from a security standpoint or of special legal relevance.

A recent example shows how much caution there should be given that the standard detectors currently available could even be abused, with error rates generally still in the double digits: After the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, the Israeli government published multiple photos of the burned corpses of babies as proof of the gruesome acts committed by the terrorists. One of the photos was erroneously flagged as fake. The terrorists then used AI to generate a new picture in which they swapped the children for dead dogs and said that was the real photo. This was intended to discredit all the other photos that were not flagged as fake by association, suggesting that the Israelis were deceiving the public.

The British royal family also had its own experience with this kind of “false positive” this past spring. All it took to touch off a firestorm of scandal was for an online detector to find irregularities in a family photo of the royals. A whole host of experts chimed in that there was nothing suspicious about it, just standard photo editing like the kind many amateur photographers do, but their voices were almost drowned out in the breathless reporting.

With detection of fakes still that error-prone, a different method can help to at least recognize the originals: “The only strategy people can be relatively sure of today is a positive signature: Newer digital cameras leave a cryptographic signature in their pictures that is difficult to falsify. There are also cell phone apps that do this,” Steinebach says. “Big tech companies are also working on new security strategies in which, like with blockchain, all of the steps in processing an image are signed and stored, for example.” The royals and others should be pleased to hear that.